Forum: Poets and Borders

Editor’s Note: On January 25, 2017 Donald Trump signed an executive order for the construction of the border wall. As many of us protest against yet another thoughtless act of Trump’s presidency, it might be useful to ask: what is border life? What does citizenship mean today? What is language of the border? This forum began as a series of private letters between poets who live on US/Mexico Border as well as those who have traveled far and wide; as the conversation grew, others were invited to share their perspectives. For the sake of space and overall cohesion, several responses have been edited and/or condensed.

History of poetry is a history of border crossings. We learn our craft from banished poets (Ovid, Dante, Milosz, Tsvetaeva, Bei Dao, Darwish, etc.), from poets who spent years of their lives on both sides of borders, or within prison walls, or in lines to prison walls, or in camps of various kind (Wang Wei, Hikmet, Akhmatova, Lorka, Mandelstam, etc), from poets who watched their people migrate by thousands, and yet proclaimed, as Boris Pasternak did, that “poetry transcends the borders, smashing those borders.”

–Ilya Kaminsky

What does that mean to live on the border? What is border life?

Nylsa Martinez (b. Mexico): To live on the border, in my experience, means to not be aware that you have been living between two countries: it is just a fact, a part of an ordinary life. Then, when you start growing up, you realize that you are not part of the usual checklist of nationalism requirements or characteristics. You notice that, there are many things that you referred or remembered as part of your childhood, without a Mexican stamp on them. The way you have named things since you have memory, the food you have eaten, music, TV shows, are an strange combination of two sources. People from the center of Mexico might have said: “You´re not a Mexican”.

But my grief of border-life is my mom’s funeral: the story of retrieving her body from USA and taking it across the border for the funeral in Mexico.

Ming Di (b. China): Political borders are the strangest. Why does Tahiti belong to France? Why does Hawaii belong to the US? They are geographically far away from their rulers. Why do Latin Americans speak Spanish even after they declared independence? Why do Yi people and 54 other nationalities in China speak Han Chinese? How many languages around the world have died or are dying? Languages should be cherished and preserved. They are borders but can be crossed.

Once, I lived on a labor farm with my parents. We lived on corn and potatoes, one egg per household a day, no rice, no milk or meat even though there were many cows around. There was a political border between people like my parents living in restricted bungalows and the rest of the farmers who lived in their own homes—they were not allowed to give us chickens or green vegetables. Then we were sent to a remote countryside because even the bungalows were regarded as too good for people who returned to China from overseas—they should be punished more for having lived outside the country as diasporas. China finally re-opened its door in 1979. We can move back and forth now. But there have been many labor farms in China for various reasons, many political borders within a country.

To take a larger look: Chinese emperors liked to build borders and walls. A few months ago a group of international poets climbed up the Great Wall in Beijing to read poetry. It was my idea to go up there to demonstrate “words without borders” through translation but then it made me depressed for weeks. On one hand, the Great Wall is the only thing on earth that one can see from moon, something that represents the ancient “civilization”. On the other hand there are statistics showing how many people died when building the wall and how many people were killed from the wall: millions of human bones have been found underneath the “great” wall.

Jorge Ortega (b. Mexico): Border life is living in two different countries at the same time, but in the limits of these both countries, which means a polarized version of them, precisely because of the boundary conditions.

Sandra Alcosser (b. USA): Writers have permeable boundaries. It is an occupational hazard that Milosz describes in Ars Poetica:

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

I live on two borders. One, a wilderness area shared by Montana and Idaho where, by law, over a million acres of earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.

My work as a professor places me 18 miles from the second border in Tijuana. Border issues are part of our daily conversation at the university and in the region. An undergraduate fiction writer who works as a border agent drops by my office to say goodbye. She says she is moving to Canada, even though she hates the cold, because never again does she wish to open a car hood in Tijuana and discover a child hidden, singed and hugging the engine.

Even the brain has a barrier that protects it from toxins. Each eye a border, each ear and fingertip, and as beings who happen to be readers and writers, we flow across boundaries, searching for equanimity.

Martin Camps (b. Mexico): To live on the border means to see the Franklin Mountains in El Paso from the window of my home in Ciudad Juárez. My eyes cross the border every morning, like the birds, and the tumbleweeds.

Life on the border means standing in line, showing your passport, answering questions, what were you doing in Mexico? Where are you going? I was breathing in Mexico, I was eating. I am going to see my sister in El Paso. It means to be searched, scrutinized, questioned. Bridges that don’t cross rivers, like in Tijuana, they just cross rhetorical rivers, the waters of fear.

On the Tijuana border it used to be that the people would get close to the border and talk, people would meet their families from the other side. But the Border Patrol created a “no zone”, an in-between space, so now it is impossible to meet the people on the other side. It bothers me that people die trying to cross the border, that there are people thinking that they are better than them because they want the US to be a gated community and believe in fallacies such as “good fences make good neighbors”. We already have a fence. Imagine that you build a 10 foot wall with your neighbor, that is a statement, a monument to hatred.

On the Tijuana border it used to be that the people would get close to the border and talk, people would meet their families from the other side. But the Border Patrol created a “no zone”, an in-between space, so now it is impossible to meet the people on the other side. It bothers me that people die trying to cross the border, that there are people thinking that they are better than them because they want the US to be a gated community and believe in fallacies such as “good fences make good neighbors”. We already have a fence. Imagine that you build a 10 foot wall with your neighbor, that is a statement, a monument to hatred.

Corinne Goria (b. USA): I can only speak about San Diego borders, this special and suffocating corner of the United States and of the world, hemmed in to the south by a wall and an electrified fence and a hundred kiosks and a thousand surveillance cameras, pressed from the north by the relentless gloss of Hollywood and from the east by the vast, indifferent desert. And then, there, glittering beyond dull buildings like a wide oasis in pavement, the Pacific Ocean. Living here feels like we’re caught between three devils and the deep blue sea.

I grew up in east county San Diego, where the border patrol trucks were green and white and everywhere. They had tinted windows, and cruised slowly, and you never saw an agent unless his truck was parked with three others, stopped in the street amid orange cones that blocked a two lane highway. They asked for your driver’s license then. They looked in your car and in your trunk and under your car. It was September and 85 degrees and you were supposed to be home already. As you broiled in the glare you grew restless and resentful.

Now I live closer to downtown. We are perched on a median of land above the 805 and the 15. Every morning, cars muddle through the highway on their way north. Every afternoon, they do the same going south. At night, if we stand in the middle of our street – a street that ends in a playground but used to run all the way to the border before the highway 15 was built it up – and look south, we can see Tijuana. We see the hill sharply rising from the Tijuana river valley; bejeweled in electrical light, houses crowded together on the face of the mountain, staring back at us.

Last night I had to tell our 17 year old babysitter, a U.S. citizen, and her mother – a mother of four U.S. citizen children, a woman who has been in this country for nearly 20 years, her whole adult life, but who is undocumented – about what I’d heard through the immigration lawyer listservs. Raids happening in the shopping center in University Heights. Border Patrol agents stopping people clutching grocery bags, clutching their children’s hands. CPB arrested fathers and a few mothers.

They’re not just targeting those who’ve been deported before, or those convicted of a crime, or those who’ve had traffic violations. They’ve started arresting anyone who doesn’t have papers. Even those who’ve been told, as recently as last week, that they had a right to stay.

I’ve been trained to discuss preparation in a clinical manner: make sure you designate someone to pick up your kids from school. Make sure someone has the keys to your house to let your kids in, to make them dinner, to explain to them what’s happened. Make sure someone has power of attorney so they can sell your belongings, get guardianship for your kids, get back your security deposit. “Because you could be taken at any time,” went unspoken.

Our babysitter listened with her eyes on our coffee table. Her mother began to cry. “All I want is to go visit my own parents in Mexico. My mother can’t walk anymore. My father doesn’t eat. He doesn’t even get out of bed anymore. They don’t have much time left. But if I go visit them, I can’t come back. The only reason we’re here is for our kids. But I have to choose between seeing my parents one last time, and never being allowed back home. I just want to give up.”

Our babysitter listened with her eyes on our coffee table. Her mother began to cry. “All I want is to go visit my own parents in Mexico. My mother can’t walk anymore. My father doesn’t eat. He doesn’t even get out of bed anymore. They don’t have much time left. But if I go visit them, I can’t come back. The only reason we’re here is for our kids. But I have to choose between seeing my parents one last time, and never being allowed back home. I just want to give up.”

Valzhyna Mort (b. Belarus): In the 80s, growing up in a small isolated and landlocked Soviet country, I thought that the world unfolded towards the east: Uzbekistan, Kazakistan, Mongolia, Armenia, as well as the Far North, took up all of my imagination. The closed western border around the corner didn’t exist for a child. The world started with me and stretched into the ultimate snow on the north-east and the ultimate sun-lit steppe on the south-east.

In the 90s, the border was the Belarusian-Polish border. During the economic crisis, many people travelled to Polish open-air markets to sell whatever they could to make ends meet. My father went too, often coming back later than expected and empty-handed. I saw then very clearly that a border is neither a line nor a long tall fence, but a waiting room. It’s a waiting room with a pin-up calendar on the wall, it smells with glue and the wood of cheap pencils, there people are stripped of everything except for the meat that can sit and stand upon request.

In the early 2000, I myself travelled to Poland to take part in a translation school that met for a few weeks in Warsaw. I travelled by train. On the Belarusian-Polish border the trains were lifted for the change of wheels: the width of rails in Europe, or what we consider political Europe, is different from that of rails on the territory that at the time of railroad construction belonged to the Russian Empire. This way European trains couldn’t just roll into Russian Empire unexpectedly, in case, of, say, a war.

Lifted inside the train for a good hour, my fellow translators and I joked how those millimeters that made all the difference for the railway system, formed a true border between west and east.

Ishion Hutchinson (b. Jamaica): Perhaps border life is a wish to be borderless.

This drastically extends the concept of border, backwards and forwards in time, but the heartbreaking, spirit-breaking story of borders for me is that of the African holocaust called the Middle Passage.

There are also borders of other kind, not geographical. The imagination. It is the border that abolishes border, much like the sea, we strive in with hopes of reaching other shores.

Nikola Madzirov (b. Macedonia): The border is a sketch for the sculptures of war. It is the thickest line in the atlas.

Four decades I’ve been living among three state borders constructed by history and flags torn by the wind and wars. It’s the ideal place where one can understand the hurt of the in-between worlds and the temporariness of the absolutistic myths from the great state narratives, a place where one can touch the silence of the urge for non-belonging.

At the time she lost her job in a textile factory after the fall of totalitarian regime, my mother was earning by smuggling cheese over the border. It was revealed to me later, the moment I saw her through the bus window on the border crossing, while she was trying to hide the pieces of cheese under the thick jacket, as if she was hiding her child from war dogs. What were worth all the poetic images of the world as opposed to that moment of the secret speech of survival?

Last year I witnessed a long column of bicycles with the Syrian  refugees on their way to West European countries. I saw them as a moving border of lost memories and thresholds, recalling the rusty keys of the house that my ancestors had to leave during the Balkan Wars.

refugees on their way to West European countries. I saw them as a moving border of lost memories and thresholds, recalling the rusty keys of the house that my ancestors had to leave during the Balkan Wars.

Katherine Towler (b. USA): My husband Jim and I have taken birdwatching trips to Arizona and Texas in recent years and been on the border. It’s sobering to experience the presence of the border guards everywhere. They descended on us in helicopters when we got out of the car with binoculars to look at a hawk. They eventually figured out we were birdwatchers. It feels like a police state. At a check point on the highway in Texas, we saw a busload of Latinos, mostly women and children, pulled over. They were standing in the 100-degree heat surrounded by border guards with German shepherds. We were waved through the check point. It made me understand the phrase white privilege viscerally.

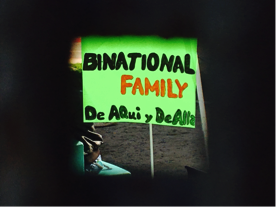

Jenny Minniti-Shippey (b. USA): In my border life, I play with the young children of an undocumented immigrant. We count horses-caballos y yeguas – chase loose conejos back into their pens, swap languages mid-sentence. At its best, border life is lived in multiplicity- you can watch and listen and feel cultures pushing into each other, making something new. I read somewhere that democracy is in part functional because we have to live cheek-to-jowl with other people, sharing services, impacted by the same public works. In that sense, border life can be deeply democratic. What happens on a border affects both sides, both countries. Border life is also one of inequality. At the park in my neighborhood, mid-day on a Wednesday, the women are brown and the babies are white.

Hari Alluri (b. Nigeria): A border life is a multiple life. Of cuts, of proliferations.

Recently, riding the bus one day in San Diego, CA, U.S.A., Kumeyaay land, I ended up sitting opposite a man who, as we rode through City Heights on El Cajon Blvd., told me that if I were to walk down a major artery in the neighborhood, I would notice the languages and origins of the mostly mom-and-pop shop signs read like a history of U.S. military incursion and intervention overseas. I have and it does. For example: Chile, Vietnam War, Iran-contra, Iraq, Somalia, Sudan, and more. That neighbourhood, with its arteries and cross streets and shop signs, is a story of borders, of cuts.

Edgar Rincón Luna (b. Mexico): I will be brief. Those of us who inhabit the Mexican border are the survivors. We cling to the edge of our country because we don’t wish to leave it, but various circumstances forced us to be here. The border is filled with immigrants. I am the child of immigrants. The city is filled with immigrants from other cities, all of them fleeing something, survivors of natural or economic disasters of their country.

The prejudices are from our border. Skin color. Accent. Place of birth. When violence increases, the media accuse those who live among us yet who were not born in the city. There’s also prejudice about social class. The poor are deemed as thieves. They’re vicious. They have no future. The rich are all corrupt, or are accused of abusing their power, and are termed as racists.

Breeann Kirby (b. USA): The neighborhood I live in is one of the oldest in San Diego; it’s a beautiful pocket of eclectic houses with old trees and wide yards, full of history. And full of money. An address gives its residents a certain level of privilege, which can manifest in a type of closed-off isolation from things that could be challenging.

One personal story I have is that I took my son when he was four to the beach at the border fence. We were utterly alone on an empty beach, the windshields of border patrol cruisers parked on the ridge above us flashed in the sun. The fence at this particular place consisted of rusted posts like rotted teeth jutting out of the sand into the surf. South of this fence, families were picnicking on the beach while little kids swam around the fence posts like little remoras around a shark’s teeth. My son wanted to go play with the kids and couldn’t understand why, when there was nothing physically stopping us, I wouldn’t let him get closer. As he sobbed, I kept looking up at the border patrol. I was frightened of the consequences if I let my son engage with these children. I think my fear caused both myself and my son lose something important that day. I never want fear to keep me from engaging with people.

One personal story I have is that I took my son when he was four to the beach at the border fence. We were utterly alone on an empty beach, the windshields of border patrol cruisers parked on the ridge above us flashed in the sun. The fence at this particular place consisted of rusted posts like rotted teeth jutting out of the sand into the surf. South of this fence, families were picnicking on the beach while little kids swam around the fence posts like little remoras around a shark’s teeth. My son wanted to go play with the kids and couldn’t understand why, when there was nothing physically stopping us, I wouldn’t let him get closer. As he sobbed, I kept looking up at the border patrol. I was frightened of the consequences if I let my son engage with these children. I think my fear caused both myself and my son lose something important that day. I never want fear to keep me from engaging with people.

Hayan Charara (b. USA): Among my Arab friends and family members, there’s a common story that most have lived a version of: because of war or a so-called “travel ban” (Donald Trump was not the first to impose one), these people go years—even a lifetime—without seeing their homelands, or the people still living there.

Between my parents, for instance, they went decades not being able to lay eyes on their parents because where they called home the United States deemed hostile.

His entire life in the United States, my father lived and talked like someone in transit—that his life and home in Detroit was temporary, that a more permanent life and home was in Lebanon. Eventually, he returned. But it took him nearly forty years to get back.

But when he got back, he found an entirely different country; the country had changed so much, he might as well have gone to another planet. He’d changed, too. The most heartbreaking aspect of this story: just a couple years after he returned, yet another war broke out, a literal shattering of the illusion of home which he held onto for half his life.

And yet I want to speak of the happy stories, too. Every individual, every family that manages somehow to live in one place and still think of and call another place home—they and their stories are inspiring. I say this because in actuality, tragedy comes easy; you find it at every turn. To see the beautiful in it, in life, this usually requires more imagination than most people think possible. And yet, they do.

Gabriel Rubi (b. USA): Language flows freely like goods between borders. No taxes for language unless you consider those who fabricate walls solely on account of your accent as taxing.

Here is a story: my cousin and her husband who lived here on a work visa filed their renewals with an attorney. The attorney failed to file and requested more money to correct his own mistake (essentially a bribe to keep my family in the United States.) They did not have the money and my cousins were ultimately deported. They were not allowed to apply for a Visa until ten years as a result of their expired visas. Their children, my younger cousins, lived with my parents until they were eighteen. For a decade, the family is fractured as a result of this one corrupt attorney looking to steal from immigrant families.

Here is a story: my cousin and her husband who lived here on a work visa filed their renewals with an attorney. The attorney failed to file and requested more money to correct his own mistake (essentially a bribe to keep my family in the United States.) They did not have the money and my cousins were ultimately deported. They were not allowed to apply for a Visa until ten years as a result of their expired visas. Their children, my younger cousins, lived with my parents until they were eighteen. For a decade, the family is fractured as a result of this one corrupt attorney looking to steal from immigrant families.

Here is another story: my father was running an errand during a rainy night. He saw a man and his five year old daughter under a highway bridge in Otay. They obviously crossed illegally and they were trying to get a hold of their family in Los Angeles. They could not reach anyone so my father seeing that the young girl was freezing with a shivering lower lip, took them to our house. My parents fed them and the daughter took a warm bath. They eventually got a hold of their family and stayed the night until the family picked them up the next day. No fear of theft or violence, this is simply what people do with citizens of the border. They thanked my parents and offered their own house if they were to ever visit Guadalajara. Our family never took them up on the offer, but we got Christmas and thanks cards for the next few years. That was more than my father expected in return.

Carlos Kelly (b. USA): Border life is family. Carne Asadas on birthdays, any celebration we feasting, don’t forget the cigarette fest outside with Tios y Tias, primas y primos, lighting-up, while children run around and frolic, happy because parents are busy in their gossip. The border is real Mexican food, a family tree deep in its Tijuana roots, a trip through memory lane, schools pops went to, a nostalgic love that used to call me gringo, Mazatlan born residencies in Tijuana suburbs, the border es mi gente. The people from the Border Patrol police my dreams, me telling lies about where were you questions, bowling sir, American Citizen, the fear is real now such green made to remember, as a child I understood my Pops and Moms were undocumented—documents before Trump signed his orders, Ma did so she could vote for Obama.

My father spent his youth in miserable poverty in Tijuana, and later went to Mazatlan to live with his father. My pops has been working in TJ for almost 40 years, and crossing the border in the ridiculous lines (that sometimes range from 2-6 hours daily)—all because he wanted to give his family a better life in America.

Karla Cordero (b. USA): To live along the border willingly is the tangible, spiritual, phonetic, and historical celebration of self. To live on the border is to recognize a land that once had no border, in which the ancestors of my people would harvest the earth for nourishment. To live along the border is to recognize how a history of oppression has segregated the earth from its people. And in that history to know the border has become a political space that shadows its people. To live not on, but to live within the border, is to dance with great balance among the political entities that demand and navigate my body through this world. To be part of a language that code switches, to pray to La Virgin de Guadalupe, to be a multitude of things, to be Mestiza.

I currently work in Mexicali with a shelter called “Casa Del Migrante” (Home of the Migrant), a space that houses migrants for 3-4 day periods. The people who stay at the shelter are those who have traveled hundreds of miles from the interior of Mexico in preparation to cross the United States in search for the “American Dream.” Others at the shelter have been recently deported from the United States, broken from their families.

I visit these shelters and provide writing workshops in which migrants have the opportunity to tell their stories. The workshops conducted consist of mostly men from 15-60 years of age. To see a room of men cry is heartbreaking which speaks to their solitude. It is in these moments that leave my purpose as a writer helpless yet necessary. The stories these men share are narrated by the pictures they keep in their pockets. During the writing workshop, the migrants give their families names and faces.

Philip Metres (b. USA): The word “border” comes from the Old French word bordure, meaning, “seam, edge of shield, border,” according to the dictionary. Indeed, a border is often a shield’s edge. It was first used in the geopolitical sense in the 16th century to describe the division between England and Scotland. And that’s what I usually think of—the line that separates two countries, two states. Gloria Anzaldúa’s great book, Borderlands/La Frontera, reconceives that space in ways that opens it up again, despite the walls that states construct to shield or push out. She writes: “The U.S-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country — a border culture.” It is place where peoples and languages and cultures commingle, creating something else. I love that she crosses tongues here in talking about this third country, a place of wound and lifeblood all at once.

space in ways that opens it up again, despite the walls that states construct to shield or push out. She writes: “The U.S-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before a scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country — a border culture.” It is place where peoples and languages and cultures commingle, creating something else. I love that she crosses tongues here in talking about this third country, a place of wound and lifeblood all at once.

I’ve never lived literally in the borderlands (I’ve tended to find myself more at crossroads), but I’ve crossed many literal and figurative borders. Post-9/11, Arab American, I’ve been nervous at borders, at airport checkpoints, trying to fix a face that might pass for pacifist, that might be allowed to pass. Once, in late 2001, crossing into the United States from Canada, I recall answering the American border guard’s question where we were living with “Cleveland, Indiana.” A place that doesn’t exist. Somehow, my fear-scrambled brain combined the places that we’d lived most recently, creating another, third place. I gripped the steering wheel tightly, as if it might steer itself away if I weren’t holding it there.

Traveling in 2003 to Palestine, where my sister was due to be married to a Palestinian man from the little village of Toura, we’d been told by my sister to say that we had come to The Holy Land as tourists to see The Holy Sites. This strategy might, she’d told us, spare us the special interrogation, which involves hours of luggage plundering, incessant cross-examination, and humiliation. Despite my pose as a tourist, from her high perch, like a judge before the accused, the passport control guard stared at me the way the sun narrows its glare through a magnifying glass. “And where are your grandparents from?” she asked, the way acid eats through glass. “And your great-grandparents?”—as if to determine the potential layers of criminality and terrorism that might be sleeping in my DNA. Yes, my father’s side is from Lebanon. Bsharri. Dayr al-Qamar. Yes, that makes them—and me—Arab, though probably they may have thought of themselves as Phoenician, or Christian, or Lebanese, and one great-grandmother had flaming red hair and green eyes. Such distinctions melt before the rational paranoia of the great-grandchildren of pogroms and the grandchildren of the Shoah. “And where will you staying?” she persisted. My sister had told me nothing so that no one could be incriminated. “A hotel?” I said, shrugging. I was the worst fake tourist ever. Shaking her head in disapproval, but having, no doubt, recorded my optical signature for future reference, she let me pass.

What does it mean to be a citizen? Can one be a citizen of a border?

Jorge Ortega (b. Mexico): The borderland is a country itself. I think of these two lines by Mexican poet Jose Gorostiza: “No es agua ni arena / la orilla del mar”. The seashore is neither water nor sand.

Ming Di (b. China): Citizen doesn’t mean anything to me unless I’m traveling but even when traveling poetry is my passport.

I love the concept of “citizen of a border” because I don’t feel that I belong to any country. I am a citizen of border in the diversified California without walls: I am part of Asian communities, part of Latino communities and part of Afro-American communities. But in reality, “citizen” means “country”. What is a country? One side of a war wins and draws a line around its territory.

Sandra Alcosser (b. USA): To be a citizen is to take one’s place in the human order of things and hopefully to contribute something of value.

It’s a slow political process, but as our former poet laureate Robert Hass said:

Thoreau read Wordsworth, Muir read Thoreau, Teddy Roosevelt read Muir, and you got national parks. It took a century for this to happen, for artistic values to percolate down to where honoring the relation of people’s imagination to the land, or beauty, or to wild things, was issued in legislation….I think that the job of poetry, its political job, is to refresh the idea of justice, which is going dead in us all the time.

Nylsa Martinez (b. Mexico): Life in the border is constructed by little pieces from this and that from both sides. You cross, buy, visit people, as a quotidian act. You complain about dealing with the US customs, to be force to smile and pretend everything is fine, to wait an unpredictable amount of time to go across. But at the same time, this sense of border citizenship is not just filled with items purchases, it is more a deeper conscience. You know for which country you belong to, but you aren´t sure about the stickers you want to put in the bumper of your nationalist spirit car.

Nylsa Martinez (b. Mexico): Life in the border is constructed by little pieces from this and that from both sides. You cross, buy, visit people, as a quotidian act. You complain about dealing with the US customs, to be force to smile and pretend everything is fine, to wait an unpredictable amount of time to go across. But at the same time, this sense of border citizenship is not just filled with items purchases, it is more a deeper conscience. You know for which country you belong to, but you aren´t sure about the stickers you want to put in the bumper of your nationalist spirit car.

Jenny Minniti-Shippey (b. USA): I think citizen, maybe at its most ideal, means a person who is invested in their community. Whose actions show an awareness of and an interest in improving the place they live. I think about the term “civic duty” as aligned with “citizen.” That there’s a duty to others-and to your place-in being a citizen. So in that context, absolutely, one can be a citizen of the border. For me, at least, living in a border city has expanded my understanding of who my community is in this city. It’s not just the people I know, or the people who are like me. It’s people whose lives I have difficulty imagining: we share a place in the world. I become a better citizen as I learn more and work harder to try to improve this place for all of us.

Edgar Rincón Luna (b. Mexico): To be a citizen of the border means to live at a halfway point. The geographic boundary, in the case of Juarez / El Paso, is where you become a citizen of the border once you commence crossing one of the bridges, either on foot or by car, and you spend minutes or hours crossing, and if you do so on a daily basis, like students, or women who clean houses, or those who work on the other side, you become a habitual crosser, you recognize the people selling things alongside those crossing the border, you recognize the people cleaning windshields for change, the people who cross at the same time that you do, and we become a floating city that moves in two directions.

I remember a story of an adolescent boy killed by a border patrol agent in 2010. The boy chucked a rock at the agent, across the Rio Bravo, from the Mexican side of the shore, and the agent shot him, with the bullet striking the boy’s head. Another story is that of two children who were asphyxiated while waiting in the bed of their parent’s pickup truck. We understand that this occurred because of the long wait to cross the border; the authorities said that it was simply due to the truck’s mechanical problems.

But there are happy stories, too: the story of my family. My father was granted amnesty in 1990. He always worked in demolition and removing asbestos. My sister, the youngest in our family, is now a Spanish teacher at a high school in El Paso. She’s the one who inspires me most, for she teaches to adolescent Americans the language of our parents.

Carlos Kelly (b. USA) We are a people that are not limited to American representation—we are so much more. For me, the people associated with the San Diego/Tijuana border are unique citizens, because we inhabit two worlds daily.

Nikola Madzirov (b. Macedonia): With the slightest fear inside me I’ve been walking through the no man’s land between two borders – a space in which there are no statues of heroes, no endemic plants. I’d like to be a citizen of this nameless area, that invaders cannot rename it.

The borders in the Balkans have been changing more frequent than the fertile seasons of the plants or the dynamics of the historically imposed hatred. I remember how in my childhood my father was asking us to keep silent while passing the border crossing. I don’t know whether it was a silence of obedience to the uniform of the customs police officer or it was a silence of the common fear from the initiation rite of crossings. Such silence was most powerful on the borders, where an aerial war between the frequencies of the various state radio stations was waged. I wanted to be understood by no one, I wished I couldn’t understand the languages when I was at a border crossing. This new language embodied in silence – interrupted occasionally by the sounds of stamp upon the passport – was the brightest evidence of presence in the album of the returns towards oneself.

Philip Metres (b. USA): Borders are notoriously porous; no wall  ever holds everyone out. The Great Wall failed to keep the Mongols at bay. The Maginot Line was crossed. Consider the tunnels of Gaza—whole cars and brides smuggled through. My passport is blue, and I try to live a political life according to and beyond the ideals of the Constitution. But I am a citizen of the earth and verse, of oxygen and lung, of the hurting and longing, of hoping against hope.

ever holds everyone out. The Great Wall failed to keep the Mongols at bay. The Maginot Line was crossed. Consider the tunnels of Gaza—whole cars and brides smuggled through. My passport is blue, and I try to live a political life according to and beyond the ideals of the Constitution. But I am a citizen of the earth and verse, of oxygen and lung, of the hurting and longing, of hoping against hope.

Every time I attempt translation, I feel something in me transported elsewhere, beyond my own skull’s borders, like some figure in a Chagall unmoored from earth, somewhere between thrill and terror.

Martin Camps (b. Mexico): Benedict Anderson said that we live in “imaginary communities”. What does “Mexican” or “American” mean? I believe that all human beings have planetary rights to cross borders, to live where they want to live. But borders exist to preserve a world order, the ones that have and the ones that don’t. We have borders even in our cities, living in the “nice part of the city” and not going to other parts where the “undesirables” live. We have shadow borders in every American city.

Ishion Hutchinson (b. Jamaica): To be a citizen, strictly speaking, is to belong to a state, which, from an official standpoint, is always suspicious of duality. “But,” Auden says, “Love, at least, is not a state,” and I think that speaks to being a citizen of a border, without fear of either side, unwaveringly in love with both.

Here are two last lines of Auden’s “Unknown Citizen”:

Was he free? Was he happy? The question is absurd:

Had anything been wrong, we should certainly have heard.

Valzhyna Mort (b. Belarus): To be born in Belarus is already to be born into an exile. It’s a country in exile from itself, from its history, its culture and language. Even it’s current name is nothing but a remnant of Russian colonization. It’s an internalized border. It shows on an intimate level too. So few families can trace their family history further than 1930ies. Beyond it is one large, pitch-dark grave, and quite literally so: in the woody outskirts of Minsk, people still find human bones in mass graves.

During World War II Minsk was completely demolished by Nazi bombardments. It was then described as kind of “gates into Moscow.” It had to stand, to protect the sacred house beyond it. In fact, the whole country was perceived as a kind of line beyond which laid the heart of the motherland, its heath. For Soviet Russia, just as for the Russian Empire before it, Belarus was a borderland, a human fence the size of a small country.

Hari Alluri (b. Nigeria): I have been deeply troubled by the word citizen, and even more so now that we are re-reminded that official citizenship is the thing people can be stripped of.

Once, at the border, an officer looked at my passport and said, “Oh, you’re one of us,” and some of the tension that accompanies me at every border crossing left me. And, I felt something in that moment, not necessarily belonging, but perhaps I experienced, momentarily untaut, what it is to feel like a citizen.

I’m troubled because this means that certain people get to feel like citizens and others do not. I imagine what I felt in that briefly untroubled moment is the opposite of what many folks identified as undesirable by their countries of origin and and/or skin and/or dress—despite judicial rulings—are experiencing right now, being told explicitly and implicitly (at borders and within them) that they are no longer or never actually were “one of us.”

I think that the word citizen itself becomes more alive when you ask if one can be a citizen of a border, partially because the border in your question becomes more than a division.

Here is a story: I had crossed the border, once, with some friends—“an Iranian woman, a Jewish woman, a Black man and myself, a brown man born in Nigeria, try to cross the border” might almost sound like the beginning of a joke—and, despite what some might consider a non-threatening reason for our crossing (“a poetry reading,” we had said), we were stopped at the border and made to wait while we were checked out in detail and we were not allowed to go to the washroom. Others, of course, face much more strenuous, violent, life-threatening and ongoing border experiences. That night, only a few months after Israel launched Operation Cast Lead, all three poets read at the public event the aching, beautiful, powerful poems in solidarity with Palestinians. During Suheir Hammad’s reading of her new poems The Gaza Suite, a part of myself opened that I had never felt opening, the part of myself I myself had tried to open during that border-condensing attack; I wailed and stomped my feet and my tears ran free; I was still devastated on our way back across the border hours later.

Having said that, I have to add that the geographical border has become more charged, cemented, policed, militarized, razor-wired, etc. through the feeling, embodiment, significance, organization and manufacture of other borders, which is also to implicate capitalism, colonialism and empire, masculinity, patriarchy, heterosexism, racism and the nation-state itself.

Having said that, I have to add that the geographical border has become more charged, cemented, policed, militarized, razor-wired, etc. through the feeling, embodiment, significance, organization and manufacture of other borders, which is also to implicate capitalism, colonialism and empire, masculinity, patriarchy, heterosexism, racism and the nation-state itself.

It is through the imagination of the border that the figure of the “illegal” has been invented. And I say invented because I believe, along with many others, that no one is illegal. That phrase itself is a kind of poetics.

Hayan Charara (b. USA): I’ve always been torn about what it means to be a citizen. While I was born here (in the United States, in Detroit), my parents were not—they came here from the Middle East; they had to “earn” the title of citizen. Technically speaking, beyond how we got to be citizens, there was no difference. But technically speaking is about the only way to see no difference.

For a long time, precisely because I was born an American citizen, I felt I did not have to worry as much as others, or even at all, about belonging—or about the benefits of belonging. As a child and even a young man, I often went along with others to immigration offices, and I was never apprehensive, or nervous, or concerned—not for myself, that is—and the only thing separating me from the person with me, who was concerned, nervous, and apprehensive, was the accident of my being born in a particular place.

That’s what I thought it mean to be a citizen—to have those arbitrary (and welcomed) benefits. Of course, I lived in a house with people who did not share this view, precisely because they a different kind of citizen, the kind scrutinized on a regular basis, who had to “prove” the allegiance otherwise presumed with citizenship.

I was dumb to think that I was immune to the same scrutiny. In this respect, the “border” that defines who or what makes a citizen isn’t geographical. I didn’t realize this—or I should say that I didn’t feel this—until later, while living in New York City, when the 9/11 attacks happened. In that moment I realized that my identity as a citizen was not nearly as cemented as I thought it was. More importantly, I realized it probably hadn’t ever been.

I didn’t feel so much like a citizen on or after 9/11—that is, I didn’t see myself as part of the “us” in the “us versus them” rhetoric and policies that followed the attacks. Not because I was unaffected by the attacks; not because I didn’t think of myself as American, and not that I didn’t think “we” were attacked (in my own case, I very much felt attacked because I lived and worked within sight of the World Trade Center). I didn’t feel like a citizen because it became clear to me what the word meant, how it was used: a citizen was not necessarily a legally recognized subject of a state, but an ideological subject of one.

That difference had existed in my life from the beginning, with my father and mother, and all the other “citizens” in my life who, long before September 11, 2001, had to negotiate the “border” between the competing and often impossible to reconcile notions of what it means to be an American.

Corinne Goria (b. USA): Sometime one learns of one’s civic duty from speaking to others. I will share this story here. I am an immigration attorney. One day, a man sat in on the other side of my desk. He had a brand new black and red baseball cap on. He had on freshly creased blue jeans. He was so soft-spoken I had to lean forward, forearms on desk, clear my throat and repeatedly ask, “Sorry? Could you repeat that last part?”

We were going through the questions on the form that he needed to submit to obtain legal immigrant status.

“Where is your mother?”

“She works in the capital. She left when I was eight.”

“Where is your father?”

“I don’t know.”

“How did you support yourself once your parents left?”

“I lived with my aunt. My mother sent home money for my schooling. And when I was eleven I started to work in the harvest.”

“Have you ever been the victim of a crime in this country, in [your country] or any other country?”

“No.”

“Did you ever experience any violence in your village?”

“No. Life was pretty good. We were just poor. And I missed my mom.”

And then this man told me how he decided to leave his village. He had no suitcase, no backpack, no passport, no lunchbox. Nothing in his pockets. He journeyed for months, hopping on the back of trains that zigzagged up through Central America, through Mexico.

“How did you feed yourself?”

“People gave me food, sometimes. They saw us on the street and gave us food.”

“Have you ever been arrested in this country or any other country?”

“No. But we were stopped at a train station once.”

“You were stopped by police?”

“Well, no, not really by police. We were waiting by the train tracks, me and maybe two dozen others. And then these two men came and they let us know that they had guns. They made us give them money.”

“Did anyone get hurt?”

“No. They just took all of our money and left.”

“So they robbed you?”

The man’s face lit up, as though he’d been trying to think of the word for what had happened and now had been reminded of it.

“Yes, that’s it – they robbed us.”

“Did they take anything from you?”

“Yes, I had 14 or 15 pesos. They took it all.”

“But you’ve never been arrested by the police for doing anything wrong?”

“Well, no, just by the immigration agents once we got through the desert.”

“How long were you in the desert?”

“I don’t know. Three or four days.”

I knew about the desert. I’d heard stories about it. People get lost. They underestimate its vastness. They underestimate its harshness. People in that desert drink their own piss to survive. People don’t always survive.

“It’s difficult, huh?”

The man’s eyes were dark and hard seemed nearly feral when he said this. His gazed at me from across a great distance.

“Yes.” I didn’t ask any other questions about the desert.

“You just had a birthday, I see. Happy Birthday! Sixteen years old is a big deal in this country. It usually means you get to drive… but, well, that’s something we can maybe talk about in the future. One step at a time.”

“Ok.”

“And I didn’t realize that you were already enrolled at [local] high school. Next time we can meet in the afternoon so you don’t have to miss school, ok?”

“Ok.”

We wrapped up the questions on the form and then, to lighten the mood, to transition quickly into a goodbye because my infant son was at home and the babysitter would have to leave soon, I said, I was stuffing documents into my bag, now – had seen the clock and was trying to get out of there quickly.

“So, how are you liking San Diego?”

Suddenly, his eyes shifted from matte, from a brutal distance, to a brilliant obsidian. “Oh I like it. It’s great. I really like the weather here.” He looked past me to the Spanish bell tower of Balboa Park, bright terracotta rising into the blazing blue sky.

“Have you spoken to your mother? Does she know you’re safe?”

“Yes, I called her at her boss’s home,” the boy said. “She knows I’m safe.”

Gabriel Rubi (b. USA): To me a citizen is someone who is always looking after the greater good.

Gabriel Rubi (b. USA): To me a citizen is someone who is always looking after the greater good.

Is there such a thing as “language” of a border? Is that a language of sounds? Images?

Martin Camps (b. Mexico): The language of the border can speak in poquito English and a little Español, in Spanglish, Angloñol, Borderñol. It can move in different imageries of American and Mexican culture. The language of the border is a scar, a mirror, a crystal, a megaphone, a whisper.

Ming Di (b. in China): Language of a border? Smile. When I don’t understand my Mexican brothers or Slovenian sisters, I smile. I smile to overcome the linguistic borders. I smile to say yes I understand you. Language of a wall? Look at Trump’s face.

Edgar Rincón Luna (b. Mexico): There is a border language: in the border, Spanglish blossoms, despite the purists belonging to both of the languages. The interesting thing is how some words from that dialect have reached more southern regions of Mexico. They now say things like Troca for truck, Lonche for sandwich, or Bloque, for a city block. Apart from that language, there’s an atmosphere made from sounds: the border patrol’s helicopters, the trains. The music. In border cities we listen to music in two languages. We can listen to Banda, drug-trafficking ballads, songs of Taylor Swift, or pop from the 80’s.

Jenny Minniti-Shippey (b. in USA): When I think of the language of our border, it’s actually the visual language of billboards. Of course, most cities work and live and speak in multiple languages, but San Diego is one of the few places I’ve experienced that advertises in multiple languages. Oh, and our radio stations. I listen to two stations that broadcast in Spanish at some times, English in others. Those are a visual and auditory reminder that our city is not monocultural, monolingual.

Ishion Hutchinson (b. Jamaica) Language of the border? It is easy to idealize such a “language” and simply call it “poetry.” But that would be wrong and risking shibboleths. There is the language of people, only, and what they do with it.

Philip Metres (b. USA): I once saw a fence in the DMZ at Qalandia Checkpoint, in the occupied West Bank of Palestine. It was clotted with plastic bags, bullied there by the wind; then one blue bag, in a strong gust, cut itself free, and floated over the checkpoint, like a nationless flag.

Jorge Ortega (b. Mexico) There are some codes, of course, of the poetry from the US-Mexico border: English words in Spanish poems, English words deformed by Spanish, Spanish slang influenced by English, colloquial Spanish from the North of Mexico melted with Mexico’s Spanish and the one from Latin America and Spain. But much further there is an imagination made of some recurrent elements: the wall, the transient city, the river as a frontier, the desert and the sea — and Mexico City in the far distance. This blend is the reason there is a peculiar and inexhaustible speech.

Nikola Madzirov (b. Macedonia): I’ve witnessed that the first sign of recognition that one has crossed the border of Western Europe to the Balkans was the rotten waste on the edge of streets and roads or the loud speech of the lovers or the taxi drivers in the early morning hours. I’ve never considered that the  waste can also be a language of crossing, aside of being a rough language of someone’s hunger for presence; that the image of peeled façades or of a laundry hung on the balcony can be visual visas for the illegal glances over the border; that the emotional tone of speech denotes a crossing of a political border. Sometimes fog covers all that.

waste can also be a language of crossing, aside of being a rough language of someone’s hunger for presence; that the image of peeled façades or of a laundry hung on the balcony can be visual visas for the illegal glances over the border; that the emotional tone of speech denotes a crossing of a political border. Sometimes fog covers all that.

The fluent borders of languages like a mercury in the thermometer indicating the preparedness of achieving a full understanding beyond all the arbitrary borders of the geopolitical processes. Brodsky said it was the language itself a result of uncertainty. Perhaps that’s why the possibility of language to kill occurs when it is used to erase the uncertain memories of childhood. It fascinates me how unreachable is the border of the shadows of the people we care for; how far can be the alphabetical borders in dormant labyrinths of libraries; the frontiers of a thought and a sight in the dark intersected by the light and sound of an ambulance…

Nylsa Martinez (b. Mexico): Language of the border? That’s my favorite part. People from the border have a whole list of ways to call things. And, to make a difference between “Spanglish”, which has an extended use in USA, and, which is more a mixture of English constructions where a few words in Spanish are inserted, anyone who has lived on the border can confirm that the Spanish spoken in Tijuana or Mexicali or Ciudad Juárez is not Spanglish. We essentially talk in Spanish, but we have many references in English. For example: “bichi”, a word to express “naked”. We probably made it up from “beach”, a place where people would like to be kind of naked. One more hilarious creation is: “Triqui, triqui Halloween.” This is the phrase used to express: Trick or treat. Halloween is a popular day in the border region. Kids on the streets go and ask for candy, and they transmogrify the English phrase: “Trick or treat”. The amazing result is that now, we do not just use it for Halloween. During the rest of the year, there also exists another Halloween-themed expression: “Ni que fuera triqui, triqui.” (Not even if it were the day of “Triqui Trqui.” ) That’s said to someone who is demanding too much from us or asking too many things. (In other words, it’s not Halloween, so don’t expect free candy from me.) I remember my first years in college, when I moved down south to Guadalajara to complete my studies. That’s when I learned how to refer to certain things in official “Mexican Spanish”, because I had only named them by way of my border Spanish with words like: “bobby pins”, “raite (for ride)”, “winnis”(for franks), and an endless list that can continue for pages.

Gabriel Rubi (b. USA) The border town of San Diego definitely has a language on its own. Everyone speaks some Spanish despite their background. The term “pocho” is used to describe a Spanish speaker who has lost the ability to speak Spanish. Jose Antonio Burciaga defines a “pocho” as a spoiled fruit. He says, “we lost our sabor, our Mexicanidad.” The tongue needs to speak and read Spanish to continue to evolve. We tend towards a focus on English because we all want jobs and it’s rare the qualifications say “Spanish Speakers Only”. This is how one loses a language little by little. But this is San Diego and the Spanish names decor our streets and the history of this community is deeply rooted in Spanish.

Hari Alluri (b. Nigeria): I want to say the border is always already multilingual. Prior to human-enfolded borders, it is river and ocean. I lived in Ibadan, whose name can be translated as the place where the jungle and the savanna meet.

Hayan Charara (b. USA): One of the challenges every person faces is to break through language and its boundaries. I want to think that this is especially the case for writers, but really it is everyone’s dilemma. We like to think that there’s a straight line that connects the words we speak or write to the meaning we intend for them. But even the ancients knew this to be untrue, or at least knew it to be a problem of language. And you don’t have to be a poet or philosopher or a literary theorist to know the problems that language poses. My little children know it. When my five-year-old asks me if he can have cake, and I tell him, “Maybe,” he gets frustrated because he knows that “maybe” does not mean only “perhaps,” or “possibly” but also “it depends” or “if you eat your vegetables”; even worse, he knows that “Maybe” can also mean “No, you can’t have cake, but I don’t want to tell you ‘no’ right now because I don’t have the patience to deal with a meltdown.”

A poet, like me, may enjoy expanding or even completely ignoring the borders of language that we’ve come to take for granted—metaphors, for instance, allow us to go far beyond the borders we know well. But borders, for better or worse, also allow for meaning to be somewhat contained. Sometimes, we need them. Right now, in the so-called age of Trump, and Presidential tweets, language is in upheaval in great part because the “borders” of language—those that make meaning easier to arrive at—are being disavowed. More than ever, the line between what is uttered and what the utterance means, is unclear. In some ways, there’s no border to speak of. To borrow an idea from a friend, this represents a crisis of language, and insofar as making meaning is concerned, when there is a crisis of language, there is also a crisis of life. When words do not lead to the truth (when they intentionally lead to its opposite), there can be no salvation, no freedom found in language.

Corinne Goria (b. USA): The language of a border? It’s a feeling. It’s a fear and a  suffocation of being under constant watch, and knowing you, or someone close to you, could be ripped from your family at any minute. And it’s also the exhilaration of avoiding that fate. Of transcending it.

suffocation of being under constant watch, and knowing you, or someone close to you, could be ripped from your family at any minute. And it’s also the exhilaration of avoiding that fate. Of transcending it.

There have been studies on “mirror neurons” – the physiology behind empathic responses to anything from salivating when you see someone else take a bite of a sandwich, to the post-traumatic stress syndrome one can experience by simply hearing about a trauma happening to someone else. And there have been other studies that show that our nervous systems respond – our heart rate speeds up, adrenaline is released – not only when we are in distress, but when we observe another person is.

Is it possible to live next door to a country and not share a community? Is it possible for people to pass back and forth through a border that is both porous and venomous, and not affect the experiences of those who do not pass through? How could it be possible, living here, to not absorb, inhale and exhale, the fear and exhilaration, the desperation, hopelessness, perseverance, hope?

I try to retain the image of the border as the great migration of monarch butterflies fluttering through and above barbed wire and chain link fences, spinning through generations on their way to Canada, on their way to Michoacán, an orange and black scarf shimmering high above the ground.

But the language of the border is also in our silences—in pauses between words, in what we do not say. Growing up in east county San Diego – a largely white, staunchly conservative suburb – separated from Mexico by a beautiful, sparsely-covered, orange and umber mountain range, you heard lots of stories. Stories about cross-border families trekking in the hills outside of Jamul, stopping to fill up plastic water bottles from someone’s garden hose. “Scared us half to death! They just appeared in our kitchen window right after we’d finished dinner. We let them have the water, they looked like they were about to die. But my dad had his gun ready, in case any of them tried anything.”

You heard mean, black-hearted jokes about an entire people, an entire nationality, being thieves. You heard mean, black-hearted, and light-hearted riffs on an entire people being poor. You heard mean, black-hearted, light-hearted ribbing about an entire people to a person’s face. This was the true border enforcement.

Border enforcement from rich white teenagers. From rich Chaldean teens whose parents had visas. From middle-aged women: well-coiffed wives of dentists and rail-thin meth-addicts wandering around the library parking lot. Enforcement was everywhere.

Border enforcement from rich white teenagers. From rich Chaldean teens whose parents had visas. From middle-aged women: well-coiffed wives of dentists and rail-thin meth-addicts wandering around the library parking lot. Enforcement was everywhere.

You heard complaints about how much the housekeeper charged and how much she stole. About how little the gardener did and how high with tree limbs his truck bed was stacked. Many didn’t pay if they didn’t show up. Many didn’t pay if they didn’t like the work, even if the worker had spent hours. Many didn’t pay if they hurt themselves on your property. Because what are those workers going to do? Sue?

Last night I told my babysitter’s mother, whom we’ve known for years, “Don’t worry. If you are picked up, you have a strong case. You’ve been here more than ten years, you have four U.S. citizen children, you have never committed any crime, you’ve never even had a parking ticket. And we’ve known you for years. You are part of our family.”

She said through her tears, “Thank you.” And then I’d hoped she would have responded, “Yes, you are like family to us, too” – to absolve me of my complacency with this wretched situation which has been going on for decades, for generations; to absolve me for living without fear in a two bedroom home with two children, while she lived with it, in a two bedroom home with four. I wanted to be absolved. But she merely said, “Thank you. Not all bosses are like you.”

Carlos Kelly (b. USA) There is a language of the border, it is a mixture of English and Spanish, at least here in San Diego. The sounds and images of the border are festive, from piñatas to brightly colored shops selling all kinds of goods, the liveliness of the people who earn a living hustling on the border. Everything is beautiful but the blatantly atrocious green of the border patrol.

____________________________________________________________

Note on translations:

All contributions by Mexican poets have been translated by Anthony Seidman, who’s given an extraordinary amount of time and energy in putting together this forum.

Nikola Madziorv’s contribution has been translated by Trajche Bjadov.

All of the border photos in these piece are by Ilya Kaminsky.

Reblogged this on Poetry East West.

[…] Journalists aren’t the only writers covering international politics: in a two-part series at Poetry International, poets from Mexico to Europe, Africa to Asia, have been discussing the roles borders play in their lives, and the way borders limit our lives physically, linguistically, and culturally. Whether reflecting on living in Texas near the route of Trump’s proposed wall or exploring the psychological borders of one’s cultural identity, these writers weigh in on what it means to be a citizen, the way language moves through populations, and how movement across borders creates vitality. You can read the forum’s first part here. […]